A Sport on the Rise

With over 190,000 registered members (a number that is growing every day), Ladies Gaelic Football is the largest participation sport for females in Ireland. The profile of the sport has also been growing, as over 56,000 people attended the 2019 All-Ireland final, the largest-ever attendance to date for Ladies Football. TV viewership also soared with over 666,000 tuned into TG4’s coverage of finals day, a rise of more than 70,000 viewers from the 2018 Ladies Gaelic Football Final.

As participation and viewership has risen, so too has the standard of play. The pace and intensity of the game has been increasing steadily over the past ten years. Players are faster, fitter, stronger, more mobile, and more skilful than ever before and standards have been noticeably higher year on year.

A young minor player progressing to a senior inter-county team now faces a huge increase in training load and intensity. Developing a good foundation in strength and conditioning at underage level can help them to cope with the increased training load, with injury prevention, and to achieve their full potential as footballers.

The Demands of the Sport

To design an effective programme for the teenage athlete, we must understand the demands of the sport and the particular needs of the female adolescent athlete.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of information related to the match-play demands of Ladies Gaelic football at senior level, with even less available for youth level. To help us design appropriate training programs at this time, we must rely on other similar field games.

We do know that Ladies Gaelic Football is an intermittent high intensity, multi-sprint, multi-directional field sport. Physical attributes such as high-intensity running, repeated-sprint ability, strength, speed, and agility, clearly contribute to performance. Generally speaking, more successful teams perform more high intensity running in matches. The frequency, intensity, duration, and rest periods of these high intensity efforts vary. Additionally, jumping movements and sudden changes of direction may elicit a high neuromuscular load. Therefore, a broad range of physical qualities including neuromuscular (strength, power, balance, and proprioception), aerobic, and anaerobic qualities should be developed in female players.

Development of Female Adolescent Athletes

During childhood, boys and girls follow similar rates of development in growth and maturation as strength, speed, power, endurance, and coordination develop at comparable rates. Consequently, both boys and girls can follow similar training programmes during the pre-pubertal years. This should focus on a broad range of fundamental movement skills and sports specific skills. However, differences begin to emerge at the onset of the adolescent growth spurt for nearly all components of fitness, with males making greater gains in most physical attributes.

Typically, the onset of the adolescent growth spurt occurs around age 10 for girls and about age 12 for boys, although this will vary considerably between individuals. PHV describes the period of time in which an adolescent’s rate of growth is at its greatest. Generally, girls experience peak height velocity (PHV) at an earlier age than boys (12 years versus 14 years). After this time, there are significant differences in almost all aspects of physical performance when comparing males with females.

We examine these differences below:

- Females reach physiological and skeletal maturity before males.

- Females have more body fat and less lean body mass than males, a difference that can be attributed to increased oestrogens in females and increased androgens in males.

- As a result of hormonal differences, joint laxity is more common in females. This predisposes them to injury of that particular joint, and the surrounding soft tissue.

- Females have less upper body strength, which even with training remains 30% to 50% less than that of males. Lower extremity strength is much closer in parity.

- Males also have greater numbers of red blood cells and levels of haemoglobin relative to women. However, relative to body size and composition, work capacity studies show that there is only a slight difference between males and females in oxygen uptake.

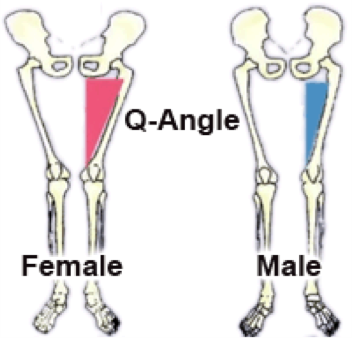

- Anatomically, females have a wider pelvis than males. This wider pelvis creates a larger ‘Q angle’. This is the angle at which the femur meets the tibia. This predisposes females to ‘knee valgus’, where the knees cave in during activities such as running, squatting, lunging, jumping, landing and cutting movements. Knee valgus is one of the major risk factors for ACL tears. Females are 2-8 times more likely to suffer this injury than their male counterparts. Such differences in ACL injury rates are not apparent prior to puberty.

- Ligament dominance is more common in females than males and is closely linked with ACL injury. Ligament dominance occurs when the muscles surrounding a joint do not perform their job of stabilizing and absorbing forces during landing, cutting and side-stepping manoeuvres and so the ligaments take over this role. The posterior chain muscles (glutes, hamstrings & gastrocnemius) are important for lower limb muscular control and avoidance of ligament dominance.

- Quad dominance is a relative imbalance in work between the quadriceps and the hamstrings and glutes during various sporting movements. This issue is more common in women than in men and is believed to be a strong contributor to knee pain and injury. Quad dominance is often seen in a straight-legged landing from a jump. Differences in male and female landing patterns emerge post puberty.

- Trunk dominance (Core Dysfunction) is the inability to control the trunk in three-dimensional space—in other words, poor trunk proprioception. Female athletes generally display decreased proprioception and allow greater movement after a perturbation or disturbance, again leading to increased risk of ACL injuries.

Importance of Strength for Female Athletes

In years gone by, strength training has been seen by many as an unsafe activity for young people. And even more so for females! However, it is now accepted that strength training is both safe and appropriate for young people when prescribed and supervised by appropriately qualified coaches.

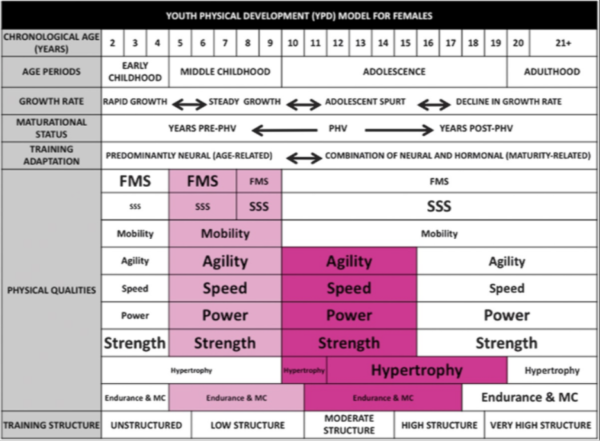

The Youth Physical Development model (figure 2 below) developed by Lloyd et al, is a comprehensive approach to the physical development of young females. It shows that the development of muscular strength should be a priority at all stages of development for females. This concept is based on research that has shown close relationships between muscular strength and power, plyometric ability, speed and agility and endurance. In addition, it has been proposed that muscular strength is important for successful FMS development. Therefore, strength development should be an important component of any athlete development program.

Developing muscle strength should be seen as an important component of youth strength and conditioning programmes not only to improve performance but also to reduce the risk of sport-related injuries. However, strength development sessions should not merely be viewed as an addition to a young athletes’ training programme but as a replacement for another form of training e.g. pitch session.

Implications for Training

So, given these differences should female adolescents train the same as males?

Broadly speaking, yes, as the muscle groups and energy systems involved in a particular sport are the same. Training programmes should be designed towards improvements in the qualities needed for successful sport performance. However, the anatomical and hormonal differences that do exist mean that when planning a programme for female adolescent athletes, there are some issues that need to be considered.

Some of these considerations include:

- Strengthening the hip abductors and external rotators which in turn will benefit potential issues further down the chain (knee & ankle).

- A strong emphasis on single leg strength

- Improving glute and hamstring strength (posterior chain) in both a double and single leg stance.

- Plyometric work. This should initially take the form of basic low-impact exercises that are aimed largely at teaching landing mechanics and control, which are then progressed.

- Core strengthening exercises. This includes both inner and outer core work.

- Training movement and stability in all 3 planes, rather than just the sagittal plane.

- Shoulder stability and upper body strength work.

Conclusion

As youth S&C coaches, our role is to prepare our players physically for the transition from youth to adult football. Often, our talented inter-county players train with multiple teams and indeed across multiple sports. Without the intervention of a sound strength and conditioning program to complement and support the player through maturation and sport participation, we leave our youth athletes open to two problems. These are overuse injuries through sport, in addition to underdevelopment through lack of strength & conditioning.

Therefore, it is imperative that a developmentally appropriate, long-term programme of athletic development takes place during the teenage years to enable a smooth transition from youth to adult Ladies Gaelic Football.

Learn more about the courses offered by Setanta College here, or contact a member of our team below.

Contact form

Bibliography:

Faigenbaum AD, Kraemer WJ, Blimkie CJ, Jeffreys I, Micheli LJ, Nitka M, Rowland TW (2009) Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the national strength and conditioning association. J Strength Cond Res. 23(5) p. 60-79

Faigenbaum, A.D., Lloyd, R.S. and Myer, G.D., 2013. Youth resistance training: past practices, new perspectives, and future directions. Pediatric exercise science, 25(4), pp.591-604.

Harries, S.K., Lubans, D.R. and Callister, R., 2012. Resistance training to improve power and sports performance in adolescent athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 15(6), pp.532-540.

Leave A Comment