Elite athlete, coach, scientist and Programme Leader of our Master of Science in Performance Coaching, Dr. Joe Warne, looks at how the threat of the ‘main effect’ can impact an athlete’s performance.

Dr. Joe Warne getting an endurance athlete’s lactate profile during a VO2max.

I realised recently, with concern that almost 15 years have passed since I first took a tentative dip into the cool waters of the Sports Science world. The area is, at best, unstable, and at worst, fickle. However, our knowledge is only evolving, and this can be nothing but positive. We are constantly trying to learn, to keep up with the never-ending stream of research being published and pushed into mainstream media. Often I feel as though the more I learn, the less I actually understand about what some would consider the “basics” of human performance, and this is a sentiment mirrored by many of my colleagues.

Often one of the challenges in sports science is the translation of complex results into a more basic understanding in order to use the implications of important research in the general public. Particularly in the last year for me, I have frustratingly observed an increasing amount of athletes who think that the main results of research will instantly apply to themselves, or believe that because an effect has been seen with a research group, the results will undoubtedly have an effect on any population it is applied to.

This, obviously, is not the case, because we are all DIFFERENT, and this understanding of individual differences makes the application of group results difficult to apply successfully. Let me elaborate with an example; In a study looking at the effects of orthotics on foot pronation, the overall effect was negligible (there was no change in foot pronation for the group), however some subjects were found to have significantly reduced pronation, and others went the opposite direction and has increased foot pronation as a result of wearing the insert. This effect goes a bit deeper here because even the effect of foot pronation itself was not found to have much of an effect on injury rates in runners, some subjects who heavily pronated were found to be less injury prone, and others were not. In this example, scientists are generally in agreement that the effects of orthotics and foot pronation do not have a major influence on running injuries, but that doesn’t mean that SOME people can find a benefit from wearing orthotics or changing foot pronation.

Dr. Joe Warne lecturing a group of Master of Science in Performing Coaching students at the SportsLab, Thurles.

On the other hand, others may use orthotics but actually increase the chance of getting injured. It’s important to remember that science, by the nature of inferential statistics, is simply trying to see a “general” trend within a group of people, but that at no point is any of these findings considered the absolute rule.

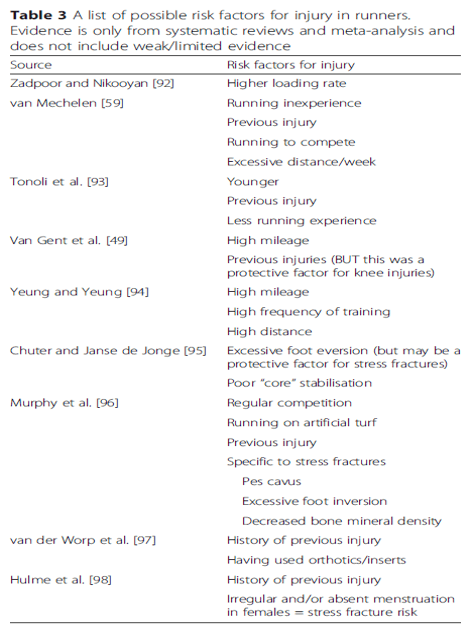

Often the most challenging area to come to any definitive answers is regarding injury. Injury has been considered a “multifactorial anomaly”, of which is highly individual and case specific. You might be mistaken to think that the abundance of injury research has led to clear idea of how to combat injury, but it appears that the more we dive into this area, the more variables we uncover that could be related. The table listed below from a recent publication from our research group summarises all of the running related injury systematic reviews as of 2017. The most notable findings from this table is not the specific factors identified, but the lack of consistent agreement between any of these reviews on what is related to injury risk. There are so many degrees of freedom in injury risk – individual athlete physiology, biomechanics, lifestyle stressors, training error, environmental differences, history etc. We cannot have all the answers, because N is always equal to 1 in real world application.

Warne and Gruber, 2017

Let me provide another example, during my undergraduate research I looked at the effect of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) on repeated 800m race performance. Sodium bicarbonate is believed to act as a “buffer” to fatigue in the muscles and is often used by 400/800m athletes as a means to improve performance. These athletes rarely test themselves to see if this supplement is having any positive effect on their own performance, but instead blindly hope that it will show an improvement, based on an understanding of the overall mechanism of this supplement. The good news from my research was that some subjects showed a large improvement in time to fatigue, able to run longer and faster when they took the supplement when compared to a blind placebo that tasted and looked the same. However, other subjects did not improve whatsoever, and others actually got worse with the supplement! It turns out that some athletes had enough of a buffering capacity that they didn’t need any “extra help”, and so these guys should look at other factors that may improve their running time instead of sodium bicarbonate. This is a great example of the complexity of an apparently simple ergogenic aid when we take the individual into account.

There are so many examples of where this concept is rarely considered. Athletes buy into compression clothing, recovery products, footwear, training programmes, diets, and so many more areas often with the blind expectation that these factors WILL have some positive effect based on reports from a group average. What actually matters is the INDIVIDUAL, and understanding what works or doesn’t work for you may involve the long process of trial and error, testing, and constantly challenging what you know about yourself or your athlete.

“The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result”

Next time that you find yourself reading a piece of science, remember that the main effect is used to inform the readers of the primary finding of the study, the effect that was most prevalent in the test being undertaken. A better understanding of the statistics will tell you more about how the subjects responded, but it would be wise to assume that there is almost always a large body of people that are the exception to the rule, and one of these could be you or your athlete.

Leave A Comment