Teenagers and Sleep

In our first post in this series, we described the negative health related effects of reduced sleeping duration for adults. In relation to the adolescent population, Orzech and co-workers (2014) provide interesting findings from their studies on this population’s sleep patterns. They examined the association between total sleep time and illnesses including cold, flu, gastroenteritis and other common infectious diseases (e.g. strep throat) during the course of a school semester. Beginning in late January, illness events and illness-related school absences were recorded and were compared among males and females and academic year groups. Results showed that longer sleepers reported fewer illness bouts. A trend was found for shorter total sleep time before ill events. The present findings, according to the authors indicate that acute illnesses were more frequent in otherwise healthy adolescents with shorter sleep, and illness events were associated with less sleep during the previous week than comparable matched periods without illness.

Teenage Athletes and their Sleeping habits

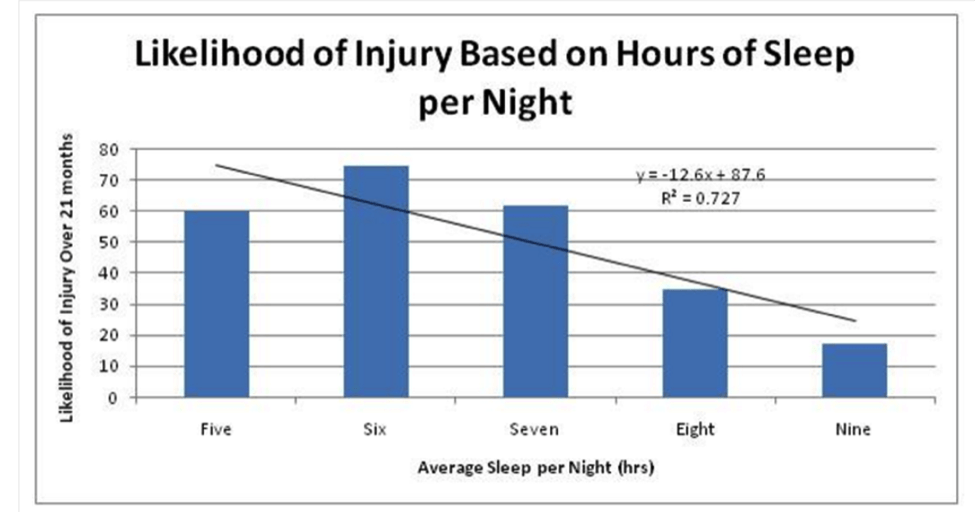

The work of Eaton and colleagues (2010) who reviewed over 14,000 adolescents’ responses to health questionnaires including questions about their sleep patterns is of interest to us as it is the first documented evidence linking reduced sleep time and athletic injury incidence. The research team found that nearly 70% of adolescents reported less than or equal to 7 hours of sleep per night. They found that only 23.5% reported 8 hours of sleep and only 7.6% reported “optimal sleep” of 9 hours or greater per night. Further, and of significance for us, the researchers reported a commonality of 72% between less sleep and injury incidence, supporting the view that reduced sleep may indeed have an impact on injury susceptibility.

More recent evidence by Milewski and colleagues (2014) highlights the association between reduced sleep and injury incidence. This team of researchers had athletic students complete an online survey of training practices. Subjects were 54 male and 58 female athletes with a mean age of 15 years and a range from 12 to 18. The results showed that the strongest predictor of injury was <8 hours of sleep per night. Please note the relative risk injury is of 2.1 here in Table 2. Sixty-five percent of athletes (56/86) who reported sleeping <8 hours per night were injured, compared with 31% of athletes (8/26) who reported sleeping approximately 8 hours per night.

Then and Now

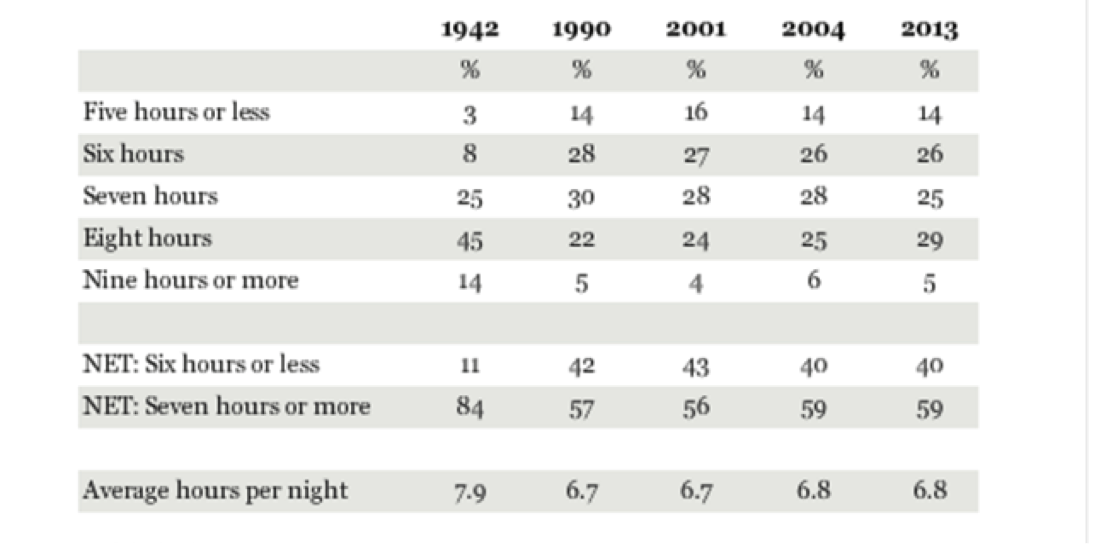

An interesting question to consider when discussing sleep is whether we get more or less sleep now compared to decades ago. Rampell (2014) described the gradual reduction in sleep duration over recent decades in adults over 18 years of age.

Note that in the 1940’s the average was 7.9 hours a night sleep. In 2013 this had decreased by over an hour to 6.8 hours per night. Interestingly, the proportion of adults sleeping 7 hours of more in the 1940’s was 84% while in recent years this has reduced to 59% of adults. So, the answer is yes we are sleeping less now compared to decades ago and more and more adults are sleeping less than 7 hours per night.

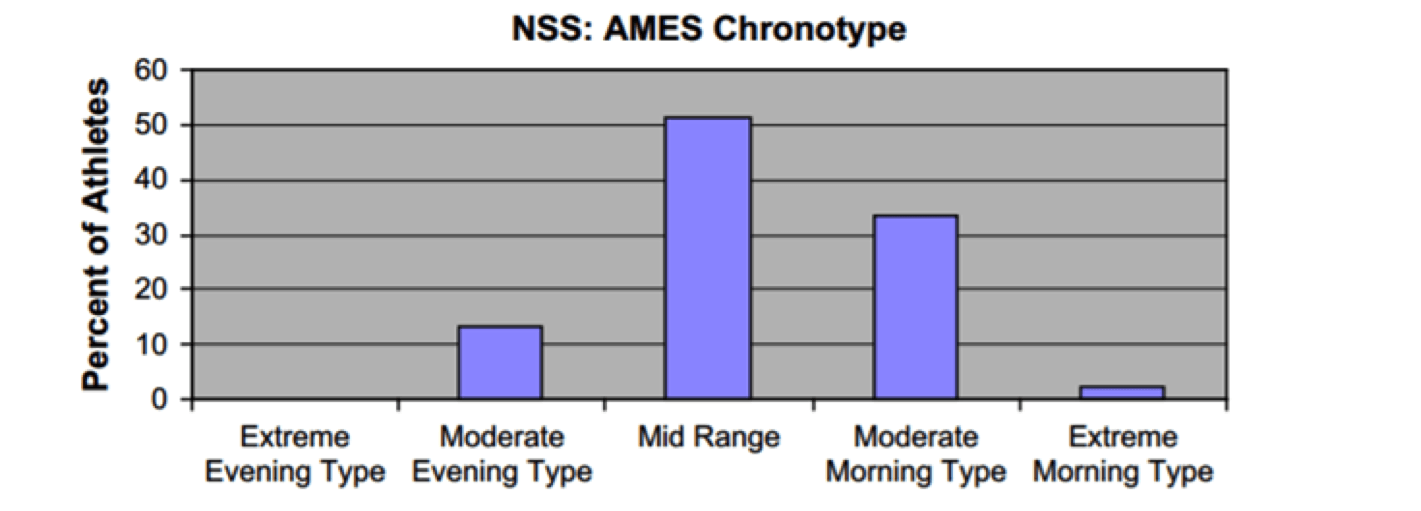

Are you a Morning or Evening Type

Samuels (2008) used an athlete morningness/evening scale or AMES scale, to determine how many adolescent and elite adult athletes were morning or evening types. This is a method of establishing what is known as ‘chronotype’. Remember that an evening type will find it difficult to get up in the morning and may have a chronic sleep debt if morning training is a regular routine. The AMES is a four-item, self-report questionnaire designed to classify the respondent’s chronotype in terms of preferred sleep/wake phase and preferred competition and training time. The AMES provides a global score within a numeric range of 10 (extreme evening type) to 31 (extreme morning type). Score categories break down in ranges as follows: an extreme evening type will score between 10 and 12, moderate evening type between 13 and 17, mid-range type between 18 and 23, moderate morning type between 24 and 28 and extreme morning type from 29 to 31. The results indicated that the majority of athletes were moderate morning or mid-range types.

Only 13% of adolescent and 14% of elite adult athletes were moderate evening types, and there were no extreme evening types. Samuels notes this night owl tendency still occurs in at least one out of 10 athletes, and should be evaluated and addressed in individual cases in order to improve sleep-related training and performance issues.

Circadian Phase

As you are well aware, circadian rhythm has a powerful impact on performance. In addition, the circadian timing of sleep directly affects sleep length and sleep quality. The circadian phase is both genetically and environmentally determined in humans (Vitaterna et al 2005, Viola et al 2007). Further, each athlete has a preferred sleep schedule that suits his or her circadian phase; however, training, school, and work commitments can have a substantial impact on the athlete’s ability to match the circadian phase to the sleep schedule. If the circadian preference and sleep schedule are not matched and are out of phase, this will affect the amount and quality of sleep an athlete gets. For example, night owls or evening types who prefer to go to bed later (say 12 midnight or 1 pm) and sleep in (until 8 or 9 am) and who then have to wake up at 5 am to train at 6 or 7 am will curtail their sleep by 2 to 4 hours per night, missing critical periods of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and slow wave sleep.

Coming up next in this series…

In our next blog post in this series, we will ask whether athletes get more or less sleep compared to non-athletes, we will also look at the sleep patterns of our elite and Olympic athletes – they should be good role models in managing sleep.

Leave A Comment